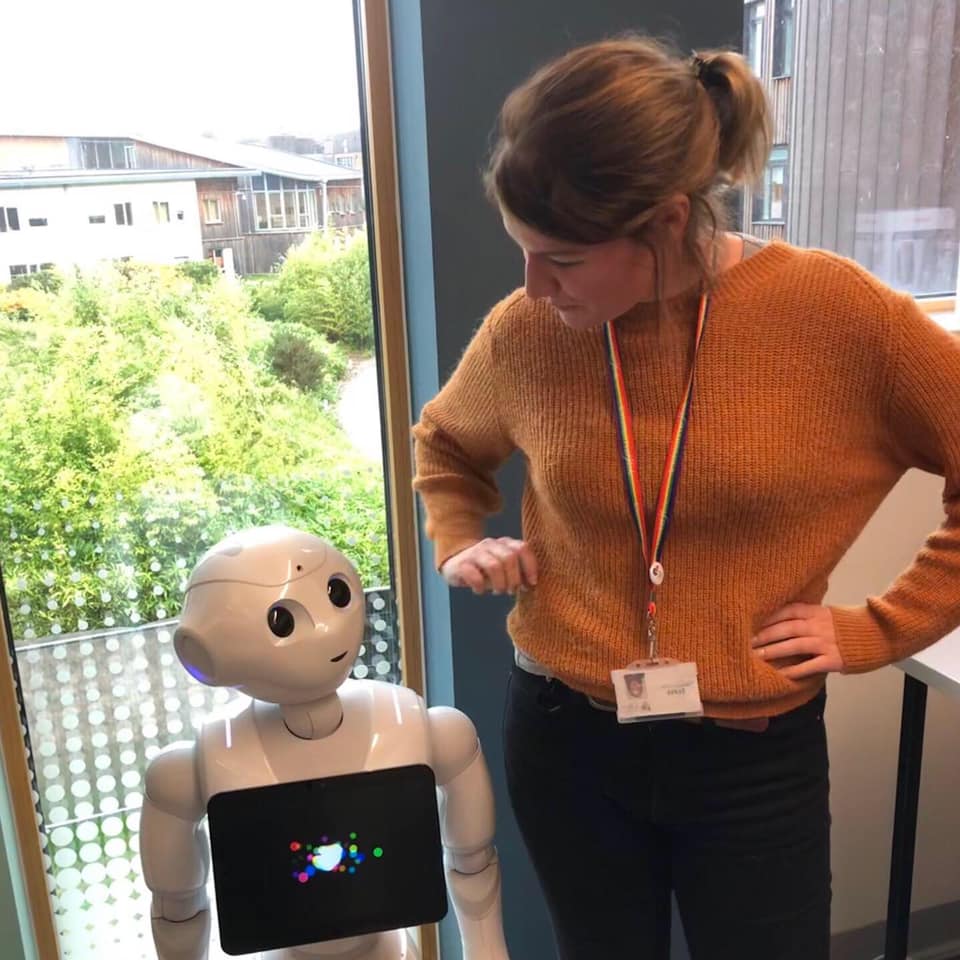

Hi, I am Jenn – a researcher looking at attitudes towards the Future of AI and this is Pepper – a semi-humanoid robot. Pepper can recognise faces and respond to basic human emotion and was built to engage people through commands and through ‘his’ touch screen. Pepper is used in schools, hospitals and businesses to welcome people and inform people.

I met Pepper in the University’s Computer Science Lab at the University of York. Pepper’s head was down and on command, Pepper was awoken, by a trusted owner in the department. The head lifted up and eyes began to flash. Scary eh? Well, that depends on who you ask.

I immediately decided Pepper was a girl, I assigned female pronouns to her – perhaps it was her cute face or her slightly high pitched voice. Though, I am since informed, ‘she’ is a ‘he’…

And I was excited to interact with Pepper. Many of my colleagues however, were not! You see, Pepper’s hands have a kind of human-like ability to move and as ‘he’ ‘thinks’ they move and even fists can be formed. Pepper’s hands are even a different texture to mimic a ‘skin’. My colleague said that even though this was an attempt at some kind of embodiment for positive reasons, this made her even more scared of Pepper and she referred to Pepper as #scary # creepy and #evil.

Whilst this was initially mildy amusing for us all, the reality is that Pepper is actually rather limited and shows no sign of ‘rising up’ against us any time soon (though if it were to, I’d rather be on it’s side). But the mix of reactions towards Pepper was stark.

On the one hand, I was excited, amused and interested, on the other, my colleague expressed complete and visceral fear of the unknown, probably born out of commonly held public perceptions of what we see in film and on TV when we see or hear the words ‘AI’ or autonomous systems and robotics.

There is a fear and this is understandable. With respect to Pepper, this is largely because people might assume Pepper is a General AI, capable of human intelligence but the truth is Pepper is what is known as a narrow AI which basically means it can support humans in solving problems only in specific cases. All too often the fear comes when people assume we have General AI and that systems are capable of Superintelliegnce or the ‘singularity’ – this is half the problem. The fact is that even the experts do not know when that will happen, if at all and it certainly hasn’t happened yet.

It is important to note then what Pepper is and is NOT. Given that there is such a lack of coherence in defining the term ‘AI’ across the academic community, it is little wonder that the public struggle to define it, or instead conceptualise of it as machine learning or deep learning – when both are subsets of what we might group under the umbrella term ‘AI’.

Importantly then, there is an emerging field of research and an increased sociological/ philosophical interest into how the public view AI and indeed, what that term even means to people. Some academic research investigates these narratives about ‘scary robots‘, while others have surveyed experts to find the mean forecast as to when General AI / human-like AI may be expected.

According to research, the median estimate of respondents was for a one in two chance that highlevel machine intelligence will be developed around 2040-2050, rising to a nine in ten chance by 2075… so soon, but not SO soon? And even then what that intelligence looks like is likely far less a dystopia than many would depict (Muller & Bostrom et al, 2014).

But what does emerge as important are key issues pertaining to (though this is not exhaustive), matters of gender stereotyping and algorythmic bias, embodiment, kinds of intelligence, forecasting, risk, regulation, emotion, and more.

And so AI and its many forms is ubiquitous and its effects could be profound and there are vast differences in the publics’ and expert conceptualisations, perceptions and emotions about AI and its uses and effects. It is no surprise therefore that research institutes, centres, universities and companies all over the world are keen to accelerate research into the potential benefits of AI over the coming decades.

As we see increased investment in research and dialogue between academia, policy actors, industry and the public, forecasting the implications of AI, exploring these myths, hyperbole and dystopian thinking that often dominates debate around the future of AI over the coming decades seems never more vital in order to achieve positive outcomes.